I came across a curious piece of press photography when exploring the TRC’s online archive. The image shows five German prisoners of war from the First World War participating in a spot of needlework whilst a crowd of spectators, also POWs, gather around in fascination, peering over each other’s shoulders to watch the exercise.

'The treatment of German wounded: Exercising the muscles of the arms by means of embroidery.' The Manchester Guardian 1915. (TRC 2021.1342).

'The treatment of German wounded: Exercising the muscles of the arms by means of embroidery.' The Manchester Guardian 1915. (TRC 2021.1342).

The embroiderers seem to be using large frames, leant against indoor tables, that have been taken outside into a daylit courtyard. This, I suppose, is to make use of the natural light and to ease the eyes when focusing on intricate work. By examining the uniforms of the embroiderers and onlookers, we understand that the men seem to be of various ranks and provincial units of the Imperial German Army. There are many officers present - signified by the scattered amount of sharp rimmed caps. The men look healthy and well-fed: something we don’t often equate with the Prisoner-of-War camps.

Sampler worked by John Robert Ratcliffe, when he recovered in hospital from a German mustard gas attack (source: http://theshuttle.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Ratcliffe.jpg).By 1915, there were 26,900 German civilians and military personnel detained on British soil, many of whom had been captured on the Western front. Prisoners were kept captive within residences across England, most famously at Donnington Hall: an 18th century manor house where officers were supposedly waited upon by those in ranks below and enjoyed leisurely activities such as croquet, hockey and self-organised theatre productions. They allegedly drank abundantly and ate well.

Sampler worked by John Robert Ratcliffe, when he recovered in hospital from a German mustard gas attack (source: http://theshuttle.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Ratcliffe.jpg).By 1915, there were 26,900 German civilians and military personnel detained on British soil, many of whom had been captured on the Western front. Prisoners were kept captive within residences across England, most famously at Donnington Hall: an 18th century manor house where officers were supposedly waited upon by those in ranks below and enjoyed leisurely activities such as croquet, hockey and self-organised theatre productions. They allegedly drank abundantly and ate well.

The photograph was published in 1915 by the Manchester Guardian, the predecessor of The Guardian. It is a glimpse into a world in which the British public are consciously aware of an alleged luxury treatment towards German military on British soil and yet tackling with widespread wartime hostility and likely personal anger due to experiential loss of life.

The text accompanying the image reads ‘The treatment of German wounded: Exercising the muscles of the arms by means of embroidery work’, which seems to have an undertone of sarcasm. Despite the obvious anti-German sentiment existing in Britain, German prisoners did seem to have been treated well within British POW camps and so I take a moment to envision the journalist who wrote this. I wonder if he was angered by the idea that the enemy was enjoying leisure time upon his “soil and homeland”. Contrastingly, perhaps, he may have relished in the emasculation of the enemy - the soldiers enjoying needlework in the sunshine may have been a wonderful joke for the publishers and readers.

For centuries before this photograph was taken, embroidery was seen as a female pastime. So, it’s perhaps surprising to see the masculinities of the soldiers, their harsh profiles mottled with the courage of war and clad in sharp tailored uniforms, contrasted against the softly meditative, ‘feminine’ craft of embroidery. Perhaps there is a greater metaphor here, embroidery being a visual signifier that they, the soldiers, are out of action (OOA) and are emasculated, reduced through humiliation to imitate the “weaker sex”. This could signify a performance of domination by the British wardens over the German POWs and, to emphasise this point, there is evidence that British POWs were embroidering in German camps.

The Khaki altar cloth: An altar superfrontal worked in cross stitch on linen, made by the Khaki Club in the Abram Peel Hospital by wounded soldiers in 1917/1918, now in Bradford Cathedral.However, soldiers creating needlework when OOA was a global phenomenon throughout WWI and hospitals and places of healing often facilitated therapeutic embroidery as a means of muscle exercise and general wellness (compare also the aspect of trench art and the Bradford Khaki Handicrafts Club). Therefore, embroidery seems to have been seen as an effective treatment of shellshock and war related injury, even if there does appear to be a kind of harboured aggressive domination hiding amongst the practices of health and wellbeing. Perhaps it is not a passive domination of the prison wardens, but an attitude within the zeitgeist, a worldwide mentality toward soldiers who were OOA, a similar visual signifier of cowardice to the white feather: embroidery mimics the vulnerability a white feather holds in form and meaning.

The Khaki altar cloth: An altar superfrontal worked in cross stitch on linen, made by the Khaki Club in the Abram Peel Hospital by wounded soldiers in 1917/1918, now in Bradford Cathedral.However, soldiers creating needlework when OOA was a global phenomenon throughout WWI and hospitals and places of healing often facilitated therapeutic embroidery as a means of muscle exercise and general wellness (compare also the aspect of trench art and the Bradford Khaki Handicrafts Club). Therefore, embroidery seems to have been seen as an effective treatment of shellshock and war related injury, even if there does appear to be a kind of harboured aggressive domination hiding amongst the practices of health and wellbeing. Perhaps it is not a passive domination of the prison wardens, but an attitude within the zeitgeist, a worldwide mentality toward soldiers who were OOA, a similar visual signifier of cowardice to the white feather: embroidery mimics the vulnerability a white feather holds in form and meaning.

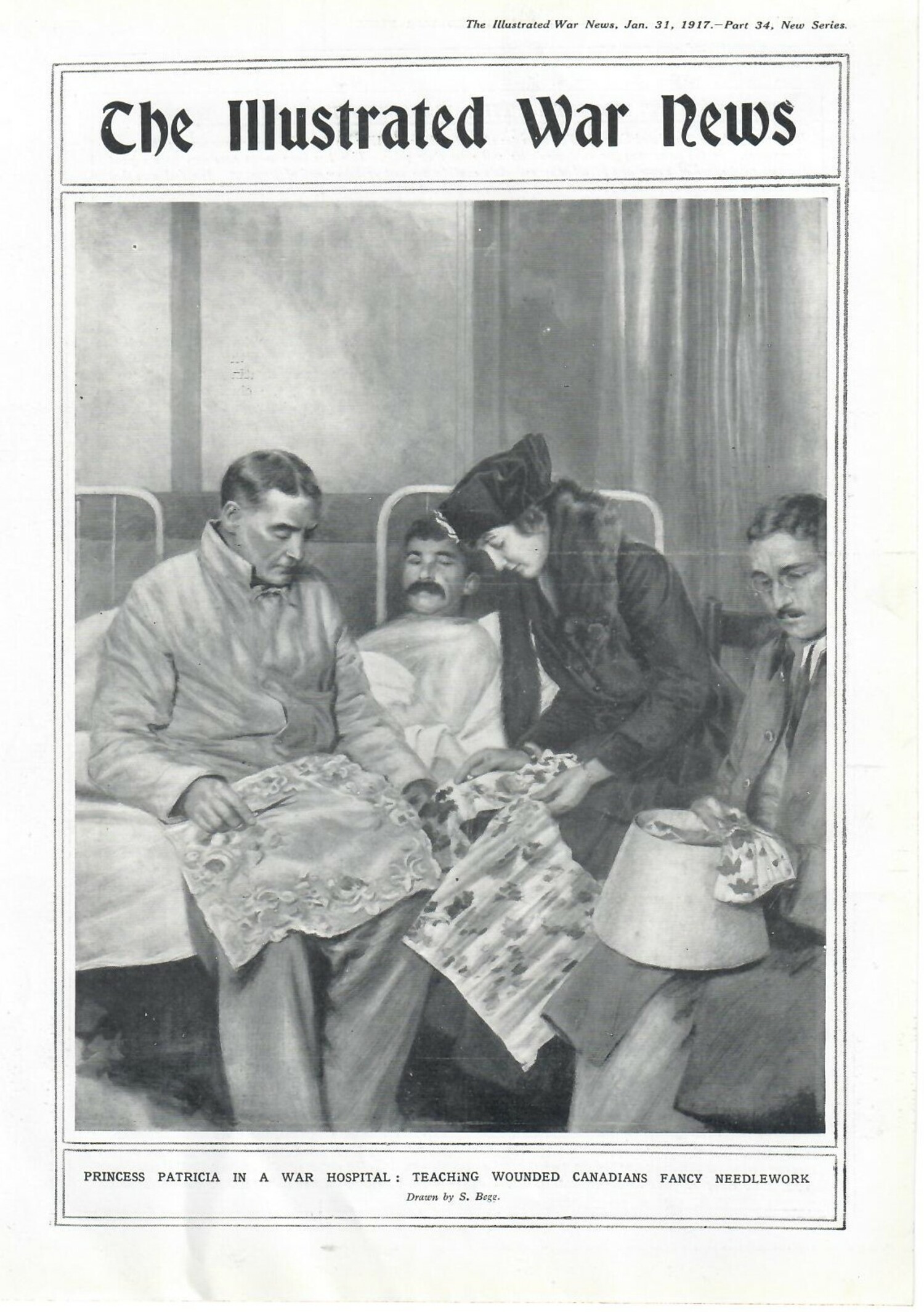

Image published in the (British) British Illustrated War News (1917), of Princess Patricia (1886-1974) teaching embroidery to wounded Canadian soldiers (TRC 2019.2381).The truth is that needlework is a healing practice, an idea fleshed out deeply in Clare Hunter’s 2019 Guardian article on sewing and healing. It has always been a meditative and rhythmic activity we can do whilst multitasking, and the therapeutic qualities of repetitive creative tasks on mental illness is widely known (craft therapy is often used in hospitals today to treat those suffering from poor mental and physical health, for example).

Image published in the (British) British Illustrated War News (1917), of Princess Patricia (1886-1974) teaching embroidery to wounded Canadian soldiers (TRC 2019.2381).The truth is that needlework is a healing practice, an idea fleshed out deeply in Clare Hunter’s 2019 Guardian article on sewing and healing. It has always been a meditative and rhythmic activity we can do whilst multitasking, and the therapeutic qualities of repetitive creative tasks on mental illness is widely known (craft therapy is often used in hospitals today to treat those suffering from poor mental and physical health, for example).

The main reason embroidery was so widespread amongst OOA soldiers during WWI was evidently because of its effectiveness in aiding the recovery of physical and mental injury - so much so that, in the shadow of the war, The Disabled Soldiers’ Embroidery Industry was established and gave those struggling a healing pastime as well as an income through the creation and sale of needlework. Practices like this still feature in contemporary British prisons too (compare the HMP Wandsworth quilt). Across each of these contexts, I suppose that embroidery is valuable, both by its nature and monetary value; a commodity yet a comfort through the soothing trance of repetition and by being so, encourages growth, change and reclamation of a sense of self in spaces where identity is all but lost.

HMP Wandsworth quilt, worked by prisoners in HMP Wandsworth, UK, completed in 2010. Copyright Victoria and Albert Museum, T.27.2010.In times of exceptional existence, where notions of normalcy are confused, interaction with familiar craft practices can enable a grounded conception of the humanness of the self. The pandemic is testament to this. It has helped us revive the hand made and re-find the key to unlocking the healing powers of embroidering.

HMP Wandsworth quilt, worked by prisoners in HMP Wandsworth, UK, completed in 2010. Copyright Victoria and Albert Museum, T.27.2010.In times of exceptional existence, where notions of normalcy are confused, interaction with familiar craft practices can enable a grounded conception of the humanness of the self. The pandemic is testament to this. It has helped us revive the hand made and re-find the key to unlocking the healing powers of embroidering.

Erica Prus, Central St Martins, University of the Arts, London