A few weeks ago Gillian and I visited the former island of Schokland, in the middle of what is now the Noordoostpolder, but until 1932 an island in the Zuiderzee, some 4 km long and 100-400 m wide. It is a weird and intriguing place, rising up a few metres above the completely flat, surrounding lands that used to be the bottom of the sea. A church, a few houses and a visitors’ centre crown the highest point of the island.

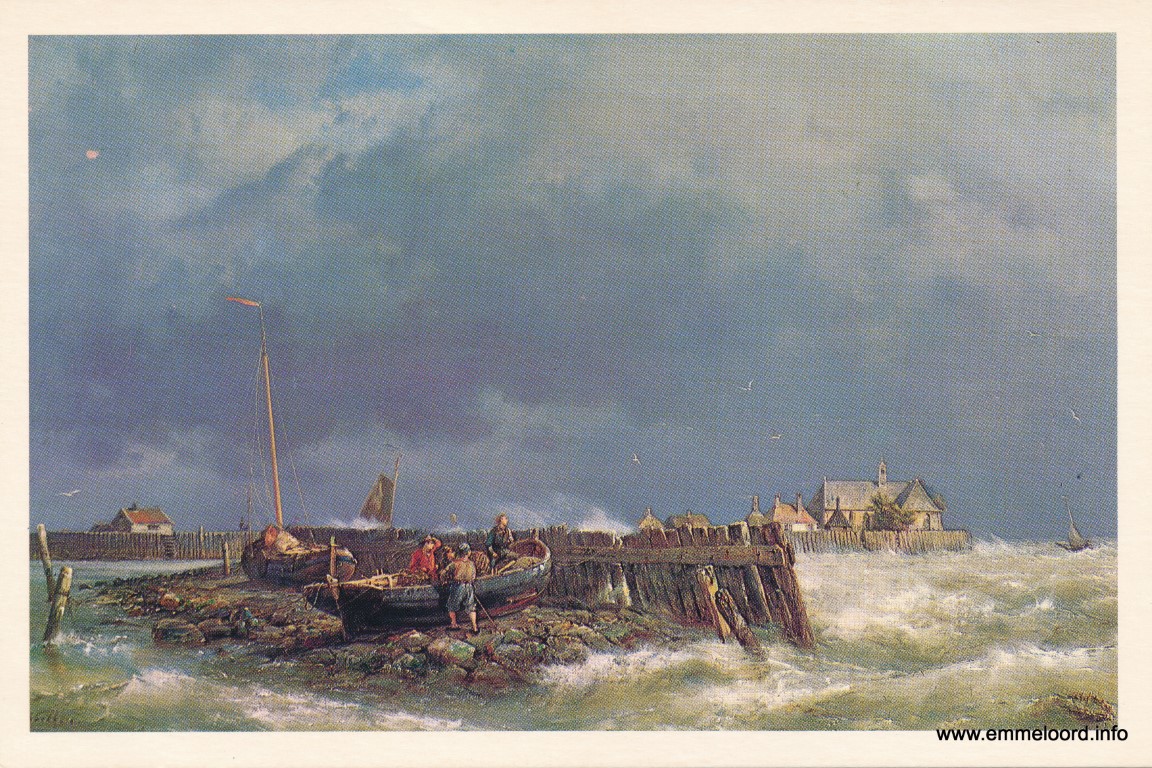

Oil painting of Schokland, by Hermanus Koekkoek (1815-1882). Public domain.

Oil painting of Schokland, by Hermanus Koekkoek (1815-1882). Public domain.

Schokland was a fairly prosperous island in the 17th and 18th centuries, with some agriculture, a fishing industry and provisions for ships from all around the Zuiderzee that anchored along its shores. By the late 18th century, there were some 600 people living on the island, in three higher areas connected by narrow sand ridges.

The island of Schokland and its church from the east.However, by the early 19th century agriculture had virtually disappeared because of the surrounding lands being flooded by the sea, the fishing industry was in decline, and other means of making a living were slowly disappearing. The flood of 1825 was particularly damaging to the island. The people of Schokland were some of the poorest in the Netherlands, and national fundraising was organised to financially support them.

The island of Schokland and its church from the east.However, by the early 19th century agriculture had virtually disappeared because of the surrounding lands being flooded by the sea, the fishing industry was in decline, and other means of making a living were slowly disappearing. The flood of 1825 was particularly damaging to the island. The people of Schokland were some of the poorest in the Netherlands, and national fundraising was organised to financially support them.

Extremely cold winters and storms sealed the fate of the island’s habitation, and by 1859 all of its people were evacuated, leaving the island virtually deserted until included in the Noordoostpolder. In 1995 the former island was declared to be a UNESCO World Heritage site.

In the local shop on the island we found a little booklet published in 2007 by Pieter Korver, De calicotsweverij van Schokland 1839-1858 (ISBN 90-72380-92-0). It tells the story of a partly commercial, partly governmental initiative in the first half of the 19th century to provide a living for the people on Schokland by introducing small-scale textile production. A detail in the history of textiles that is virtually forgotten nowadays, even in the Netherlands.

Regional dress of Schokland. Engraving published in 1857. Public domain.By the early 19th century, the British textile industry had virtually taken over the export of cotton cloth (calico: unbleached, plain weave cotton cloth named after the city of Kozhikode in southwestern India) to the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia). To counter this development, the Dutch started their own cotton weaving industry in the Netherlands. They did so in areas with high unemployment where weavers could work from home.

Regional dress of Schokland. Engraving published in 1857. Public domain.By the early 19th century, the British textile industry had virtually taken over the export of cotton cloth (calico: unbleached, plain weave cotton cloth named after the city of Kozhikode in southwestern India) to the Dutch East Indies (Indonesia). To counter this development, the Dutch started their own cotton weaving industry in the Netherlands. They did so in areas with high unemployment where weavers could work from home.

However, the ‘weavers’ first had to learn to weave, especially with the flying shuttle, which had been in use in Britain for quite some time after its introduction in 1733. Weaving schools were set up, where men, women and children were taught how to weave with the new looms, and afterwards they were engaged in the cottage industry. The company provided the looms and yarns (mainly from England) and they paid for the textiles that had been woven.

This initiative was also introduced on the island of Schokland. Two weaving schools were financed and established by the government on two of the habitation centres of the island, looms were installed, and mainly young people, boys and girls, were taught to weave the calicot fabric. As with other weaving schools in the Netherlands, the weaving schools on Schokland soon became weaving centres, subsidised by the government, where the weavers could work; this was often much easier and efficient than working from home.

The church of Schokland and the (restored) sea ddefences. Photograph Willem Vogelsang, May 2021.The calico weaving on the island only lasted for some twenty years. The two buildings used for the weaving regularly had to be repaired, sometimes because of the bad weather, but also because of the continuous movements of the looms causing vibrations that shook the buildings.

The church of Schokland and the (restored) sea ddefences. Photograph Willem Vogelsang, May 2021.The calico weaving on the island only lasted for some twenty years. The two buildings used for the weaving regularly had to be repaired, sometimes because of the bad weather, but also because of the continuous movements of the looms causing vibrations that shook the buildings.

Furthermore, in the winter the provision of yarns and other goods often came to a halt and weaving had to be stopped. In addition, the price of the finished products was continuously reduced because of the fierce competition on the world market.

In the end, the cottage industry simply could not compete with the industrialized production elsewhere. In 1852, the first steam-driven weaving workshop in the Netherlands was established that further diminished the economic viability of hand woven cloth.

As a result, in 1858, the Dutch government decided that there was no future for the people on the island, and orders were given for everyone, more than 600 inhabitants, to leave. Many went to the city of Kampen on the mainland, where a separate neighbourhood was built for them; others moved to different places along the Zuiderzee. After their departure from Schokland, most of the houses and other buildings on the island were removed and/or taken down. Only one of the original churches remained.

Willem Vogelsang, 30 June 2021.