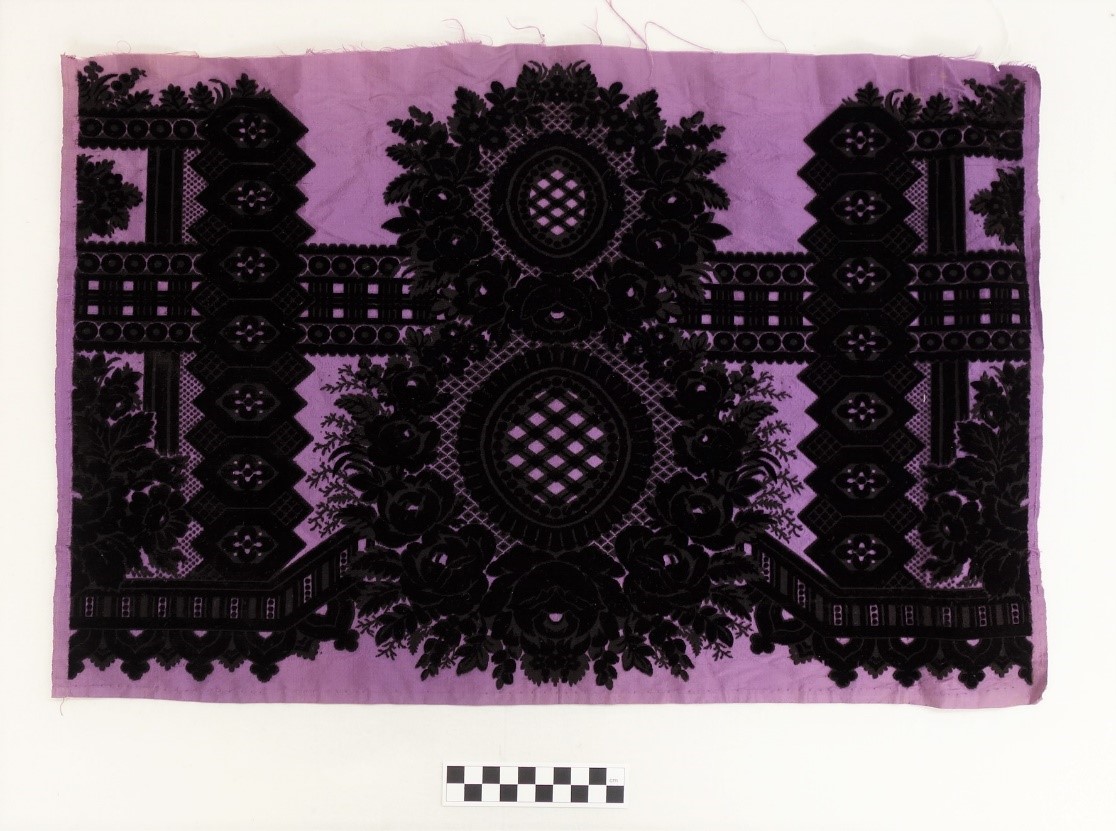

Silk velveteen made in China for the European market, early 19th century (TRC 2018.2401).The creation of a series of loops (a pile) while making a textile is not a new idea. The ancient Egyptians created piled linen textiles as early as the Middle Kingdom (c. 2000 BC). There were piled carpets at the archaeological site of Pazyryk in what is now Siberia, and these date to the fourth century BC. Their characteristic feature lies in the use of relatively short lengths of loops or tufts in the weft direction (as with modern velveteen), and not in the warp threads as with ‘proper’ velvets.

Silk velveteen made in China for the European market, early 19th century (TRC 2018.2401).The creation of a series of loops (a pile) while making a textile is not a new idea. The ancient Egyptians created piled linen textiles as early as the Middle Kingdom (c. 2000 BC). There were piled carpets at the archaeological site of Pazyryk in what is now Siberia, and these date to the fourth century BC. Their characteristic feature lies in the use of relatively short lengths of loops or tufts in the weft direction (as with modern velveteen), and not in the warp threads as with ‘proper’ velvets.

It has also been suggested that velvet is Chinese in origin and came to Europe via the Silk Road, or that it came westwards via the Mongols and their migrations in the thirteenth century.

What is more certain is that there are references to kutuf, which may have been the Arabic term for velvet, in early Arabic sources, notably to the production and use of velvet at the court of the Umayyad Caliph, Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik (691-743) in Damascus, Syria. It would appear that he and his court used both silks and velvets:

"Hisham used to be fond of robes and carpets …. In his days there were made, striped silk (al-khazz rakm) and velvets (kutuf)" (Serjeant 1973:14).

There are also references in the tenth century AD Persian geography, the Hudud al-`Alam, to katifa cloth being made in the north of what is now the Islamic Republic of Iran.

One of the earliest written European references to velvet dates from 1311 AD and refers to items owned by Pope Clement V (reign: 1305-1314), including two lengths of red velvet from Lucca. Since the early twelfth century the north Italian city of Lucca (near Pisa) had been a major producer of silk textiles of various kinds.

By the mid-fourteenth century Lucca suffered various economic problems, which were exacerbated by the advent in 1348 of the Black Death in the city that killed many of its residents. Numerous craftsmen from Lucca, including silk merchants and velvet weavers, left the city and set up new businesses in cities such as Venice, Florence, Genoa and Milan. Not surprisingly, by the end of the fourteenth century these cities had a flourishing silk weaving production that included the production of velvet. At the same time, the French king Louis XI (reign: 1461-1483) deliberately enticed Italian silk weavers to come to France and helped them set up velvet weaving centres in Lyons and Tours. The weavers were given tax exemptions (sometimes for life) in order to build up the French industry.

At the same time the Spanish court encouraged Italian weavers to come to the Iberian Peninsula and to settle in cities such as of Barcelona, Toledo and Valencia. Although all of this helped to increase the production of French and Spanish velvet, it never grew to the same status as the Italian velvet trade. Velvets from Italy were also traded with northern Europe, including The Netherlands, and velvets for the English court were shipped via Antwerp.

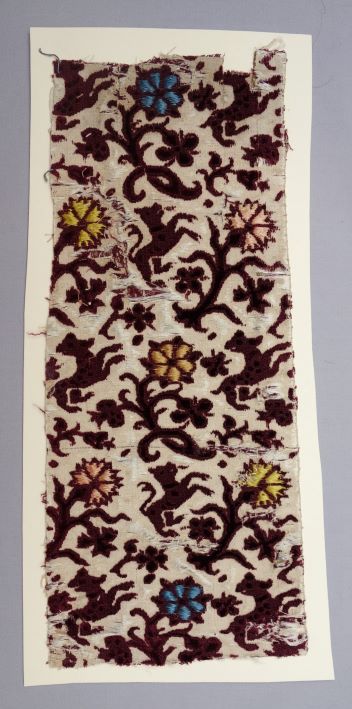

During the fourteenth-sixteenth centuries various Italian cities were also importing silk from what is now Iran and Syria and exporting silk textiles, including velvets, back to these countries. In addition, during the reigns of the Ottoman sultans, such as Suleiman I (reign: 1520-1566), for example, many velvets were made within the Ottoman empire. Yet Italian silk velvets were an important textile in court life and there are still Italian silk velvet garments housed and displayed in the Topkapi Palace Museum in Istanbul. But it was not only the Ottoman rulers who appreciated velvet. At the same time the Persian silk velvets were being produced in Isfahan, the capital of the Persian Empire. These velvets were often decorated with images of men and women in idyllic scenes representing Paradise.

By the seventeenth century plain velvets made on treadle looms and figured silks with made on drawlooms were being made in various countries throughout Europe, the Ottoman Empire, the Persian Empire (see above) as well as in India and China. But the next major change came in the eighteenth century with the advent of the industrial revolution, which meant that these ultra-luxurious textiles became more widespread and their status dropped so that they were no longer the prerogative of the elite, courts and various religious groups.

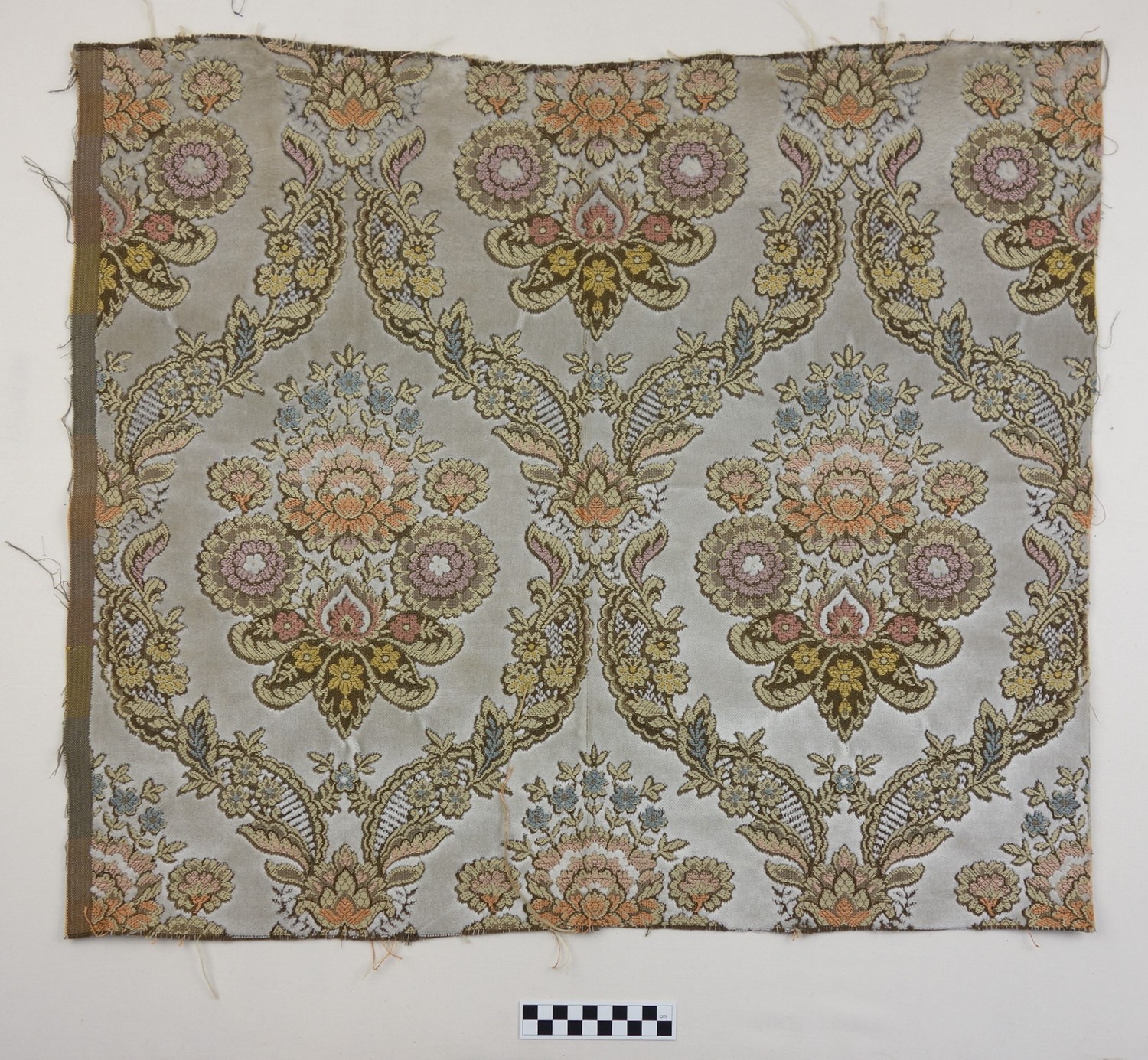

Sample of modern French velvet with a Classic mirrored design (TRC 2017.3359).

Sample of modern French velvet with a Classic mirrored design (TRC 2017.3359).

By the eighteenth century silk velvets were being produced in many European cities, now including Vienna (Austria), Bologna and Rome (Italy), London (England) and St. Petersburg (Russia). It is also likely that woollen versions were being produced in Utrecht (The Netherlands), but this is not certain. The term velours d’Utrecht may have come from woollen velvets woven in north-eastern France, notably in Rouen, where these textiles were woven on drawlooms. The Dutch word to pull is ‘trek’ and it has been suggested that velvet woven on a drawloom may have actually have been a velours de trek, from which velours d’Utrecht was quickly derived.

In the nineteenth century major changes started to take place in the production methods of velvet. More and more velvet was produced on Jacquard looms, which meant very complicated designs and backgrounds could be woven. The rate of production was also increased with introduction of wider, powered looms. A major devopment in the twentieth century was that of looms that could produce two lengths of velvet at the same time - literally face-to-face. This development made the production of velvet cheaper and thus available to a much wider consumer base throughout the world, while at the same time removing the feeling of exclusiveness. Then came the intoduction of knitted velvets with a stretchy structure. These are now often called velours. These velvets were and still are often cheaply made. Its use for velours track suits and leggings by the end of the twentieth century gave velvet clothing a poor name, a reputation that the ‘real’ woven velvets do not deserve.

- See previous chapter: Velvet! A luxurious textile in the spotlight

- See next chapter: The raw materials

Chapters: